How to reduce your dairy farm cull rate

THE PRESSURES OF CULLING

Cull cows are a sore spot on anyone`s farm. They are an issue from several perspectives: Whether you are culling on a involuntary basis or voluntary basis:

Below is some of what the cull cow encompasses:

- Production loss – Financial impact

- Transportation hazard – Veterinary intervention may be required – Animal welfare issue

IN VOLUNTARY CULLING:

Any cow that has the following conditions is beyond the point of return regarding any salvage value: Fracture of limb and/or spine, uterine prolapse, reportable disease – Rabies etc. , split , belly rupture, severe calving difficulty – blood loss, lightening strike, drowning, vaccine break etc.

These things can be called ” accidental or unfortunate” and they just simply happen on a farm. You can still ask yourself – could this have been prevented? In some cases – yes – but human control over these is really quite minimal.

Some of the above require humane euthanasia.

VOLUNTARY CULLING:

Here is the goal of voluntary culling: To manage your dairy cow herd so that you are in control of the population of cows you run. You are deciding what animals should stay and what ones should go to get culled on a regular basis with financial pressures (or liberties hopefully), production levels and animal welfare front and center.

What does your “ideal” cull cow look like:

- She is no longer going to maintain let alone improve her production level.

- She has a body condition so that there is salvage meat value for human consumption.

- She is still a valuable slaughter cow and can be transported without harm or at least low risk for harm (compromised only in some way).

- She is surplus high quality stock which you can sell to another dairyman.

- She has worked on your farm as a positive contributor to your bulk milk tank for the average period you expect/need or longer and has replaced herself with offspring.

Sound good?

It does and everyone would agree with you even a non dairy farmer. It sure sounds like the right thing to do. It is however a challenge to do this right all the time;

What happens in the real world?

Cows deteriorate in body condition and their immune system is weakened slowly over time. A result of this, conditions that are present (low grade mastitis, subclinical ketosis, respiratory disease or lameness) become worse.

For example: The animal ends up in the sick pen or special group of cows milked in the end. She is being treated. She is requiring extra attention from you and/or your personnel.

For example, the lactating cow that starts her lactation being stressed from a hard calving. She has a hard time getting up to feed, and as a result does not get enough energy and water into her which is to her detriment.

INFECTIOUS DISEASE ENTRY OR MANIFESTATION:

Two common ways of running into trouble:

FIRSTLY: Something on your farm gains hold and does damage to your cattle forcing you into treatment, or culling. The second way is new introduction by way of humans (veterinarians, neighbours, visitors etc.), service vehicles or livestock from other farms. It sounds logical, that less foreign animals coming in leads to less hazard. Remember – why are you bringing these in? Because your own replacement animals do not suffice. How do you retain more of your own replacement animals?

With a healthy cow that has the greatest possible productive longevity. The typical traditional dairy breeds advocate this – but with the downfall that muscle mass is a neglected part of the selection process in the sire program. Meet – dual purpose cattle – Fleckvieh. This breed and the sires promoted by www.betterdairycow.com have both milk volume and quality as well as muscling, substance and longevity because of this. They can weather the storm of tough times better because of glycogen reserve which acts to support them when stress/metabolic demand is high.

So – solid cattle with good “durability” will reduce cull rates which will reduce the need to bring animals in and this in turn will have an impact on health and reduce your need to treat or cull furthermore.

THE SECOND WAY: Importation of disease by human traffic: A great way to cut this down is limiting access of people of course, but some folks are necessary. For example veterinarians:

They go from farm to farm with the same vehicle. Having a dedicated parking zone with mandatory use of plastic over boots and then having them enter the barn with the coveralls provided by the farm is a sensible way to reduce or eliminate this risk. The swine industry does this for example with the added need to shower in and out in many cases. It is not costly but can save you big time.

THE ACTUAL COW IN FRONT OF YOU:

You see your cows everyday. How can you tell which one is needing to get looked at in more detail and may need to get shipped. You may suffer from “barn yard blindness” and another person can spot trouble since you are not seeing it. Slow change with you seeing the animals daily goes unnoticed. This is very natural and we all fall prey to this when we see the animals daily.

From the Dairy code of practice in Canada with additions.

Lameness

Lameness among dairy cows is widely recognized as one of the most serious (and costly) issues affecting dairy cattle. Lameness results in decreased mobility, reduced Dry Matter Intake (DMI), decreased production, impaired reproduction, debilitated cows and early culling. Some causes of lameness are related to genetics and infectious disease but the majority of problems are related to nutrition and the environment that the cow lives in. Prompt recognition, diagnosis and early treatment minimize animal welfare concerns and allow the cow to produce to her potential. The majority of cases of lameness in dairy cows involve lesions of the claw.

Genetics and actual conformation of the cow and her claws, feet and legs are more critical in the author`s opinion since a substantial amount of lameness results from weak feet and legs – like the foundation of a house. If there is weakness, it is likely to collapse. The ideal cow is “built” with an ability to bear weight and support itself with strong muscles and connective tissue support. The actual attachment of tendons and the ability to hold muscle is dictated by the shape of the underlying skeleton. Dual purpose Fleckvieh cows are proportionate in height and body structure to make movement efficient and easily tolerated by its anatomy. Overly long legs and lack of muscle tissue has been seen to result in splits. A perfect example of how anatomy relates to problems is described in some detail below based on the skeleton of the cow.

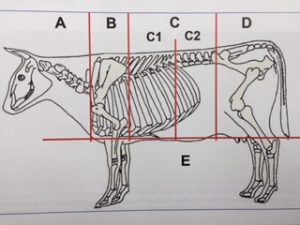

PICTURE OF BOVINE SKELETON IN SECTIONS:

The head and neck can be viewed as part of the cow. The next section is the Forequarters and withers. After that you are looking and the center piece including the loin. Second last on the list is the rump and hind quarters. Lastly – the legs. All these are the building blocks of a good (or bad) cow and reflect on performance and longevity.

Desired characteristics for each part are briefly described below:

The head should have a feminine character with a wide muzzle suited for efficient feed uptake. Goggle eyes are beneficial when there is a lot of exposure to sunshine.

The forequarter should not have a shoulder that is too steep or straight. Shoulders should be firmly attached and there should be no “pinch” behind the shoulders. We want to see good chest depth and width.

In the center piece, we want to see a wedge shape with a lot of body capacity. The rump is best when there is a slight slope to it and the width of the pin bones is not dramatically less than that of the hook bones. The legs should have hock angles of 130 to 145 degrees and be straight ( i.e. no cow hocked or bow legged rear limbs – knock kneed or bow legged in the front)

The Dairy code goes into environmental/ management factors:

- high-grain rations causing rumen acidosis and laminitis

- lack of effective fiber in the ration

- standing on concrete, especially wet and rough

- infrequent hoof trimming

- uncomfortable, poorly designed stalls

- physical hazards

- contagious diseases such as digital dermatitis

- unsanitary conditions

- poor management of transition cows

- unbalanced genetic selection (corkscrew claw) – this is a way bigger topic as described above.

Here are some useful tips surrounding lameness:

-

Gait Scoring System for Dairy Cows

Score Description Behavioural Criteria 1Sound Smooth and fluid movement - Flat back when standing and walking

- All legs bear weight equally

- Joints flex freely

- Head carriage remains steady as the animal moves

2 Ability to move freely not diminished - Flat or mildly arched back when standing and walking

- All legs bear weight equally

- Joints slightly stiff

- Head carriage remains steady

3 Capable of locomotion but ability to move feely is compromised - Flat or mildly arched back when standing, but obviously arched when walking PAIN

- Slight limp can be discerned in one limb DISCOMFORT

- Joints show signs of stiffness but do not impede freedom of movement DISCOMFORT

- Head carriage remains steady

4 Ability to move freely is obviously diminished - Obvious arched back when standing and walking PAIN

- Reluctant to bear weight on at least one limb but still uses that limb in locomotion PAIN

- Strides are hesitant and deliberate and joints are stiff PAIN

- Head bob slightly as animal moves in accordance with the sore hoof making contact with the ground PAIN

5Severely

LameAbility to move is severely restrictedMust be vigorously encouraged to

stand and/or move- Extreme arched back when standing and walking SEVERE PAIN

- Inability to bear weight on one or more limbs SEVERE PAIN

- Obvious joint stiffness characterized by lack of joint flexion with very hesitant and deliberate strides SEVERE PAIN

- One or more strides obviously shortened SEVERE PAIN

- Head obviously bobs as sore hoof makes contact with the ground SEVERE PAIN

Source: University of British Columbia Animal Welfare Program

- Routinely observe cows for lameness and aim for prevalence of – make your self establish a frequency!

- <10% for obvious or severe lameness or,

- <10% for sole ulcers and <15% for digital dermatitis

- Ensure alleyways are cleaned daily

- Ensure stalls are comfortable and that cows are lying in the stalls

- Minimize exposure to bare concrete floors

- Routinely trim the hooves on all cows as needed (e.g., twice per year)

- Balance the ration to prevent sub-clinical rumen acidosis

- Avoid feeding large amounts of concentrate in a single feeding

- Routinely use a foot bath and change routinely to maintain effectiveness (at least once daily). Check out www.thymox.com – Instead of Copper sulfate, formaldehyde this alternative is based on thymol , an active plant in gradient of the plant thyme. Approved by health Canada [email protected] or call (819)563-9298 form more information.

- Breed animals with stronger feet and legs like Fleckvieh

- Avoid prolonged waiting periods to get into the parlor for milking

HANDS ON WITH LAMENESS:

If any cow begins to look like lameness is developing, it is time to either make note of her and monitor her production levels, and body condition. Her body condition is a reflection of how much pain she is in and how much she does NOT want to eat. Ideally weighing her would be the most beneficial so she doesn’t get missed due to barn yard blindness. What do you want to know about her? When was her last trim? Is she undergoing any treatment? If you have to initiate treatment – before you do:

Go over the list above and categorize her: As a 2 she is worth observing and risking antibiotic and other therapy. As a 3 or 4 – Has she gone downhill fast? If yes she can still be shipped to slaughter without antibiotic residue. If no – increase monitoring her with treatment and hope for a good outcome.

Any animal at level 5 is a hazard to transport and needs to be put down for humane reasons.

First and foremost – a lameness combined with good body condition score stands a better chance than a deteriorating animal. They are not worth the risk you would take financially, labour input wise and animal welfare wise.

Mastitis

Mastitis is an inflammation of the mammary gland caused by bacterial infection. Most bacteria enter the udder through the teat orifices.

Mastitis is a production, food quality, and safety issue. From an animal welfare perspective, it can be a local painful infection for the cow that can, depending on the type of infection and the resistance of the cow, also cause systemic illness resulting in fever, dehydration, depression and even death.

Mastitis is recognized as a clinical infection when flakes or clots are seen in a milk sample, the infected quarter is swollen and/or hot to the touch, the milk appears thin, discolored or watery and/or the cow has a rapid pulse and loss of appetite. More often however, mastitis is subclinical. This means that infection, tissue damage, milk damage, and production loss occurs without causing visible changes in the milk, the affected quarter or the cow. Somatic cell counts are used to monitor the prevalence of subclinical mastitis.

Genetic selection to reduce somatic cell counts has been seen very successfully using the Fleckvieh breed. A healthier cow with a stronger immune system is one component of this, but also selection for Fleckvieh cows that build on their lactation volumes through their second , third and forth lactations etc. maintain much lower somatic cell counts. The onset of lactation with high volumes and then a drop after a spike in production is very strenuous for the cow`s udder. Balancing this workload over the lactation with a flat lactation curve such as many Fleckvieh breeders throughout the world are seeing makes rational sense and keeps the somatic cell counts way down.

For the development of strategic prevention programs for particular herd mastitis, infections are classified as arising from either cow or environmental sources. Mastitis caused by infections whose sources are the cows themselves is called contagious mastitis. Contagious mastitis spreads from infected cow’s udders and teat skin to uninfected cows at milking time. Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus agalactiae are the most common bacterial causes of contagious mastitis. These can be managed by teaching your milking staff proper technique and once learnt – keep it that way. Environmental mastitis occurs when bacteria from manure contaminating the cow’s environment enters the teat ends. Cows are at risk of environmental infections at all times during the day and year; hence new infections are not just associated with milking practices. Thirdly – playing into this is the healthy teat end anatomy with strong sphincter muscles to prevent bacterial entry. Genetic selection for proper test length, milk speed and diameter play an important role here.

Mastitis prevention programs are developed for a herd using knowledge of the mastitis infections the herd is most at risk of, the milk quality objectives, the facility design, current management practices, concurrent diseases, environmental conditions, and labor availability. Prevention of new infections and elimination of existing infections are the main objectives of a mastitis prevention program.

Goals are developed by a producer in conjunction with their herd veterinarian, often in a stepwise fashion, to develop an approach to improvements in animal health and milk quality.

Overall goals to strive for are:

- maintenance of a bulk tank milk SCC below 200,000 cells per ml

- reduction in the occurrence of clinical mastitis to two or fewer clinical cases per 100 cows per month (<24% of cows affected per year)

- eradication of Streptococcus agalactiae from the herd

- maintenance of a low culling rate due to mastitis.

Mastitis infections can be prevented by reducing exposure of the teat ends to bacteria. Appropriate practices should be implemented depending on the source of the bacteria identified in herd culture programs.

How to reduce your dairy farm cull rate

RECOMMENDED BEST PRACTICES

- consult with the herd veterinarian to develop a mastitis diagnostic, monitoring and control program.

To prevent contagious mastitis infections:

- dip each teat of all cows after every milking with an approved (DIN) teat dip

- ensure dip covers the area of the teat skin that had contact with the teat cup liner

- ensure infected cows are milked last or separately from uninfected cows

- implement a monitoring system using individual cow somatic cell counting and strategic milk culturing as recommended.

To prevent environmental mastitis infections:

- clean and dry teats before milking

- implement a bedding routine to keep stall beds clean and dry

- use adequate amounts of bedding to keep cows clean, dry, and comfortable

- add new, clean, dry bedding to stall backs frequently

- keep alleyways, crossovers and walkways free of manure and mud

- design stalls to give cows 12 hours of rest time

- use a stocking density of at least one stall per cow

- have all cows calve in a clean, dry maternity pen

- protect the teat orifices of dry cows during the dry period

- feed a ration that prevents stress on the immune system of fresh cows

- record clinical cases of mastitis and treatment as they occur

- assess clinical records of mastitis cases to detect herd-specific risk factors for environmental mastitis

To eliminate existing contagious and environmental infections (reducing prevalence):

- treat cows at the end of lactation with an approved intramammary dry cow preparation, as recommended by your herd veterinarian

- treat cows shown to have antibiotic susceptible infections during lactation, as recommended by your herd veterinarian

- cull cows with incurable cases of mastitis.

Transition cow – a hot spot in the lifecycle

The ‘transition phase’ begins three weeks prior to calving and ends three weeks after calving (54). The optimum management of the close-up dry cow is essential to ensure that the cow can achieve her potential in the next lactation. The main objective of the close-up period is to maintain and maximize Dry Matter Intake (DMI).

The transition phase is critical because cows must cope with a number of stressors including:

- social regrouping

- physical, hormonal, and physiological changes associated with calving and the onset of lactation

- a sudden increase in nutritional requirements.

These stressors likely contribute to the occurrence of several transitional diseases including retained placentas, metritis, ketosis, fatty liver, displaced abomasums, and milk fever. Here is where the strength breed of Fleckvieh comes through. Lower metabolic stress due to muscle reserve ends up redesign the aforementioned conditions. Delivery of the newborn calf without complication is the norm in cattle; however, cows that have difficulties (dystocia) should be assisted by a competent person maintaining high standards of hygiene and using proper equipment.

A separate calving area allows for easier observation and management of cow and calf. Close monitoring of the cow that recently calved and ensuring that she eats and drinks is paramount regardless of breed.

Tips surrounding management of the transition cow

- monitor cows close to calving at regular intervals (e.g., every four hours)

- move close-up animals into the calving area prior to calving

- give appropriate assistance where an animal is found having difficulty giving birth

- dip calf navels in disinfectant as soon as possible after birth, and repeat daily until the umbilical cord is dry

- ensure proper use of calf pulling equipment

- provide food, water, and shelter from adverse weather for cows that are unable to stand as a consequence of difficult births or milk fever. Such cows should be placed on bedding or on soft ground.

Culling 101 in a nutshell:

You can make some black and white distinction between the bad and the salvageable cases:

THE BAD: Unfit animals for transportation even to slaughter – require euthanasia or Veterinary treatment if feasible – can not be transported legally unless authorized by a veterinarian who deems a positive outcome if treatment is begun at the Veterinary Clinic

- Fractures of limbs and/or spine – no commercial salvage value – if there is timely euthanasia and exsanguination, then on site meat salvage and consumption may be possible

- Severe debilitating arthritis – severe lameness form other causes – no salvage value

- Cancer, severe cancer eye Bovine leukosis – no salvage value

- Emaciation of body condition score of 1.5 or less – no salvage value

- Pneumonia that does not respond to treatment, may have fever – no salvage value

- Rabies – no salvage value

- Large hernia – belly rupture – no salvage value

- Uterine prolapse – no salvage value – may be able to save this cow but only 50/50 chance

These are an animal welfare concern, these animals may be in high levels of pain and the vast majority can be avoided by prudent selection and genetics to build strength. Strength with Fleckvieh comes with the cow that you cross breed with but also – with better longevity, your selection pressure is lower to keep border line cases. You can ship earlier without fear of loss!

Here is a simple calculation using Fleckvieh semen for cross breeding: Firstly, you get end up with one heifer calf for approx. every 4 inseminations at $25.00 each for example. You will market the bull calf if we expect a 50/50 split between the sexes for at least $100 more than a regular “dairy” calf. Now you are rearing your new crossbred heifer, and re inseminating her mother the same way. In a period of 4 years you will end up with ( assuming the commonly seen inter calving period on Fleckvieh farms and Fleckvieh cross farms of 12 to 13 months) 2 heifers. Your original cow is now duplicated herself. She is still on your farm so you cans see her lactation performances over the long haul and decided whether or not you like this in her daughters. You are now at the point of making genetic selection choices with no pressure and you can build your dream herd.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCE:

Check out this website for more pictures and very practical guidelines form the Alberta beef code. How to reduce your dairy farm cull rate.